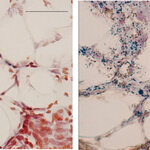

Maybe fat gets a bad rap. Immune responses matter but when it comes to skin infections, those response may depend greatly upon what lies beneath, according to a paper published in Science. Fat cells below the skin help protect us from bacteria, they write.

Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, professor and chief of dermatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and colleagues have uncovered a previously unknown role for dermal fat cells, known as adipocytes: They produce antimicrobial peptides that help fend off invading bacteria and other pathogens.

The human body’s defense against microbial infection…