Complexity and Randomness

This pattern is from System's thinker Gerald Weinberg, and has been extremely helpful to illustrate the difference between complexity and randomness. It is also a nice example of the self-referential methodology of PAC, as the pattern is used to discuss scientific approaches: science discovers patterns, which are then used to elucidate scientific processes!

Methodological Stuff:

- Introduction

- Patterns

- Patterns, Objectivity and Truth

- Patterns and Processes

- Complexity and Randomness

The Pattern Library:

Earlier, I had already argued that in complexity, we need mechanisms that builds novelty from existing things, the famous 'sum is more than the parts' type of argument. So instead of trying to explain everything from a single concept, such as 'genes', ´competition´, 'theory of everything', 'power relations' or 'the masses', we need, what John Holland calls 'building block' concepts, where new things emerge from the specific construction of underlying forms. This is one of the major differences between complexity as a paradigm, with respect to 'classical' scientific approaches, where the quest for an 'atomic' ground principle ('genes', 'scarcety', 'competition', and so on) has been replaced by one that acknowledges that a wide range of processes and phenomena may be interacting at various levels of complexity.

Most notably, complexity thinking also realises that the

'parts' may be affected by the 'whole', as patterns of feedback are at work in the network. In sociology this is sometimes called the 'micro-macro' problem, and there it can easily be observed in the fact that a 'nation' consists of people, who in turn understand that they are part of that nation (this also applies for other social groups for that matter) and therefore interact in specific ways that are customary (or adversarially) with respect to the aggregate form.

Such self-referential processes are not really in focus of traditional science, except for those areas where it cannot be ignored. Hence the tedious and fruitless 'nature-nurture' discussions continue to be waged as oppositions, while complexity thinking has no problem in understanding that it probably is a bit of both. It also

means that some methodologies or approaches may have a overly narrow focus on internal processes (nurture) while others focus too narrowly on the external interactions (nature).

In other words, every methodology, approach or theoretical framework is constrained, and the strongest methodologies are able to describe their own limitations. This is where the pattern of 'complexity-randomness'

becomes important for PAC.

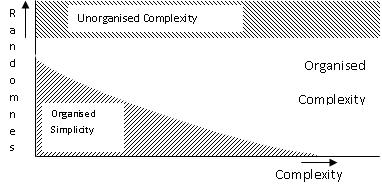

The pattern from Gerald Weinberg (at least, I was

introduced to the pattern through one of his books), depicts a

relationship between complexity and randomness:

This graph divides the subsequent plane into three

sections. The section called 'unorganised complexity' is

characterised by high levels of randomness, and can best be analysed

by statistical means. Usually phenomena in this section consist of

many, relatively simple things, that interact heavily. Think of

gases. The plane of 'organised simplicity' consists of relatively

few, strongly interacting elements, and can usually be best described

analytically. Newtonian mechanics is a good example of this. Both

planes typically describe phenomena with little uncertainty.

This leaves us with the plane of 'organised

complexity', which is the focus of complexity research, and of which

we are only now beginning to develop methodologies that can actually

be of use in that plane. Complexity theory

tends to reduce this plane to a combination of probabilistic and

analytical approaches, which has resulted in various novel insights.

The pattern called convergence inducing process that was described

earlier can be considered a good example of such a combination.

Complexity thinking

however, considers this focus to be a subset of complex phenomena

(what Edgar Morin has called 'restricted complexity'), and stresses

the importance of uncertainty, ambiguity, contingency and so on, to

be a fundamental part of complex phenomena. This does not

equate with probability, which

at best can only approximate ambiguous or contingent phenomena.

For example,

suppose that you are in a supermarket and are considering buying an

organically produced bar of chocolate. The (scientific) question now

is, in how far does your choice influence African jungle, or the

labour conditions of people working in the cocoa industry? The

statistical answer would (probably) be 'none'. You are one of

billions of people, and so your influence would be limited. However,

we also know that everyone is separated from a famous person through

a chain of maximally six relations. So a friend of a friend of a

friend of a friend of friend of a friend may be Lady Gaga who,

through this link to you, may suddenly appear on a TV show eating the same

brand of chocolate that you bought (“It was

recommended to me by a friend, it's organic and it's de-li-cious!”)

Methodologically speaking, the amplification

that is introduced through the 'six-degrees-of-separation” effect,

implies that statistical approaches are no longer valid. At best

statistics is one tool that can be used in order to answer our

research question.

However, this

does not mean that analytical

approaches will be a better choice. An analytical approach would try

to make unambiguous models of all the effects that your choice could

make. In our example, this would mean a rigourous modelling of your

social network, the social networks of your friends, of your friend's

friends, and so on. Due to the combinatorial explosion of

relationships this would quickly

become an impractical quest. As a result, we have to accept

uncertainty in the research question, which makes this a complex

question, and therefore we need to combine various approaches in

order to reduce the uncertainty. The research question what the

effect is of your choice in the supermarket lies firmly in Weinberg's

plane of organised complexity, and can only be tackled with a

balanced mix of different approaches, some analytical, some

statistical, and some involving all your creativity as a researcher,

or craftiness, in

terms of Henri Atlan.

The recognition

of the possibilities and limitations of various methodologies (PAC

included!) immediately dissolves the gap between C.P. Snow's 'Two

Cultures'. Take the next example for instance. Suppose I am

overlooking the 'Hoog Catharijne' train station in my home town of

Utrecht, and want to know the movement of people in the central hall.

The train station is one of the busiest in the Netherlands, and it

includes a major shopping mall, so I can chart the motion to the

platforms and into the shopping area. Statistical approaches will

work very well here, because the majority of people will

behave as simple particles with a straightforward instrumental goal.

They want to catch trains, or go to shops (or into town). Statistics

will be the end of discussion, because you get a certain distribution

of people over the platforms, into the shopping mall, and to the exits. Finito!

However, things

will not be as straightforward when you want to do research on, say,

voting behaviour of people (we have a lot

of political parties in the Netherlands). Statistics will, at best,

be used to reduce the number of interpretations of voting

behaviour. If there are N

possible explanations why people vote for a certain party, then

statistics will filter out a number of these interpretations at macro

scale, for instance all the interpretations that “the Dutch have

massively voted for party X because of reason Y”, when party X has

been wiped away in the polls.The interpretations themselves

have to be collected by qualitative methods, and will involve the

self-interpreations of voters on their choice. In other words,

research in voting behaviour will involve a mix of statistical,

qualitiative and hermeneutic approaches, because

it is a complex question which involves self-referential, normative

aspects of human behaviour. It also shows the friction between particular and general ('universal') issues.

A significant portion of the electorate

will not behave as simple particles regarding their voting behaviour,

and so statistical approaches become less dominant for such research

questions (however, not useless!). As a result, voting behaviour of a

nation's electorate will (have to) combine methods from both sides of

C.P. Snow's 'Two Cultures' (as I think often is already

common practice with such research questions). Weinberg's pattern

gives a reason why this must be the case.

The pattern

'complexity-randomness' can assist researchers in finding out which

methods/ theoretical frameworks/ approaches can be used to tackle a

certain research problem. If you are dealing with well-known,

relatively few elements with little uncertainty, then analytical

(deterministic, reductionistic) approaches will work perfectly. If

you are dealing with large amounts of relatively simple particles

with little uncertainty, then statistical approaches will be the way

to go. If you are dealing with research questions that involve a

large number of relatively complex interactions, or involves high

levels of uncertainty (i.e. complex problems), then a balanced mix of

various different approaches is required.

Choosing a singular

approach for such complex questions, will be like the famous joke,

where a drunkard is spotted trying to find the keys to his house

under a lantern post. When a by-passer asks if he is sure that he

lost the keys there, he answers “no, I lost them a bit further down

the road, but at least there's some light here.”