The cover of Time magazine 3/2/15 features an Anglo baby (so

remarkably cute one wonders whether he isn't a computer generated composite of

everything we like about babies) with the statement (not question, statement)

THIS BABY COULD LIVE TO BE 142 YEARS OLD.

This suggests that inside the magazine, there might be

something, perhaps a scientific breakthrough, which could support that headline. But none is forthcoming. The series of articles runs for

nearly 20 pages of confused reporting on things that may or not be happening

and a constant mis-understanding of the difference between lifespan and life

expectancy. I know you already know this, but let me just say it, so I feel

better: lifespan is how long the animal lives, based on fricking forever

evolutionary mechanisms; life expectancy is how long members within the animal

species can expect to live. As more individuals in the species get closer to

the longest possible lifespan, the life expectancy grows and the two numbers converge.

But popular, and sometimes scientific, culture gets these

two ideas confused:

- "No one lives forever, no one. But with advances in

modern science and my high income level, it's not crazy to think I can live to

be 245, maybe 300." -Ricky Bobby, Talladega Nights (movie 2006). - "Scientists believe that the first human being who will

live 150 years has already been born. I believe I am that human being."

-Chris Traeger, Parks and Recreation (TV program 2009). - "You will have a flexible career structure, you'll be

able to go back to work after forty years of retirement and become a rock star

for the next forty years." -Aubrey de Grey (Tedx 2012)

Aubrey De Grey is a Cambridge grad (originally, I said Oxford and was corrected by Dr. de Grey himself - just one of those lazy American mistakes) who has started a

non-profit organization to fund gerontology research in California. He is

obviously a genius, almost too smart to give a good TED talk. But that doesn't

mean that he is right about how we die. He views the human body as a machine,

an admittedly very complex machine, that good science needs only to practice

the right maintenance on to ensure long health. He is said to have proposed that the first human to live to 1000 has already been born, but I can't find a reliable source for that one and he certainly must have added a "in principle" or something of the sort.

De Grey is in good company in the "genius who thinks

weird things about metabolism" department. Linus Pauling, who won two more

nobel prizes than I ever will (Chemistry 1954, Peace 1962), was a bit

obsessed with Vitamin C. He died in Big Sur, California at the age of 93,

having promoted the anti-oxidant properties of Vitamin C as a hedge against

cancer and other baddies (his 1970 book Vitamin

C and the Common Cold is why many of us grew up with that categorically

ineffective treatment for viral respiratory illness). I am assuming it's not

worth space elucidating the arguments against vitamins for either colds or

cancer. What's interesting here is, why would such smart people get befuddled

over the simple distinction between lifespan and life expectancy? The answer, I

think, is that the geniuses aren't confused, they are just hopeful. How do you

tell someone like Linus Pauling that he's not onto something? The guy

essentially codified how we think about modern chemistry, invented artificial

plasma, almost nailed atomic structure of DNA around same time as Watson and

Crick...

The disease model which drives our current thinking in

medicine rests upon the idea that each symptom or discomfort is due to a

proximate cause. Either something foreign acting on the body, or a breakdown of

normal physiology. Medical "cures" involve correcting the breakdown,

removing the foreign process, etc. It is an engineering model and works pretty

well for things like kidney stones and fever. Very good scientists who have solved difficult problems in other fields are likely to think that that death is just a problem to be solved, like anything else.

For the people who are trying to (let's just listen to how

this sounds) stop humans from ever dying,

that means figuring out what the proximate cause of cell death is. One such

proximate cause seems to be telomere dysfunction. I must admit I tried to

include a few paragraphs on telomeres in this spot, but I don't want to get

into a detailed argument about a concept that is wrongheaded. Let's just skip

ahead: it's not going to be the telomeres.

Why? Because the complexity of the body does not allow for

any single simple solution to be the on/off switch for death. If it were that

easy, we likely wouldn't be here. Complex organisms are composed of such

complexity because redundancy, feedback and adaptability lead to survival. Switch

the telomeres and I promise it gets noticed and fixed, or causes worse

problems.

I wish these geniuses would go work on the common cold, or

baldness, or how about the almost universal problem of presbyopia. I say,

presbyopia first, all other age problems after that!

I had a college professor who taught a course in Greek and

Latin lit in translation. He had a problem with the difference between lifespan

and life expectancy. He frequently reminded the students things like

"Remember the Greeks died at an average of like 35, so when Achilles and

Odysseus go to Nestor for advice, you've got a 35 year old who's the elder

statesman, advising a 21 year old in a fight with a 16 year old..." Now,

Homer, writing (or actually rapping) around 1000 BC doesn't deal in hard

numbers, but it seemed obvious to some of us students that wise grey bearded

men of those days were likely similar to wise grey bearded men of the present

day...perhaps 60 years old. But our professor would never give in on this

point. Strangely, there is quite a bit of evidence from the period of which he

had expertise that can help to disprove the myth that we are living longer

today than ever before:

Plato invokes Socrates (469-399 BC) at age 70 saying, after

he hears his death sentence:

"If you had waited just a little while, you would have

had your way in the course of nature. You can see that I am well on in life and

close to death." - from The Apology

In The Republic, Socrates recommends that rulers in the

ideal state should be over the age of 60. An idea that is presumably based upon

the concurrent Spartan government. In this system, 2 kings (so one could go off

to war while one stayed safe) joined 28 men over the age of 60 to govern the

city-state. 60 was chosen as the minimum requirement as it was the age of retirement from military service for the

Spartans. (H. Mitchell, Sparta -

Cambridge 1952)

We can take these facts as indicating that men lived a

similar length of life in ancient Greece as they do today (and in the case of

Plato's ideal Republic, women too). In fact there is

documentation of the longevity of at least the richest Athenians of the time

when Socrates roamed the streets arguing with people. In a 2008 paper examining

the lifespan of famous aristocratic Athenians, Menelaos Batrinos

"identified 83 whose date of birth and death have been recorded with

certainty." They found a mean length of life of 71.3 +/-13.4 years. It is

the "+/-" that concerns us here: How long did the longest living men

go, in a time without vaccines, antibiotics, chemotherapy . . . pants?

In a nice table, which I don't want to steal for this

article, Dr. Batrinos shows that among the 83 men, ten of them lived longer

than 90 years, three of those were centenarians and one, Gorgias (who must have

been that same Gorgias Plato portrays hangin' with Socrates?) lived to 108

years old. We have no reason to suspect that Gorgias was the longest lived

Greek ever, he is simply someone for whom we have a number. Considering that

our most recent record holder, Jeanne Calmet (French) died at 122 years old in

1997 and was famous for no other reason than this, we seem to still consider

these ages shockingly long. In fact, the current oldest known age at death for

any man is 116 (Jiroemon Kimura, Japan 2013), just 8 more years than Gorgias

from 483 BC.

I think this makes the chances for Chris, Ricky, Aubrey and

that Time baby to reach their goals seem quite slim indeed.

The myth of unlimited scientific progress, as applied to medicine,

is based on the fact that life expectancy (not lifespan) has been rapidly

improving, especially in the last century:

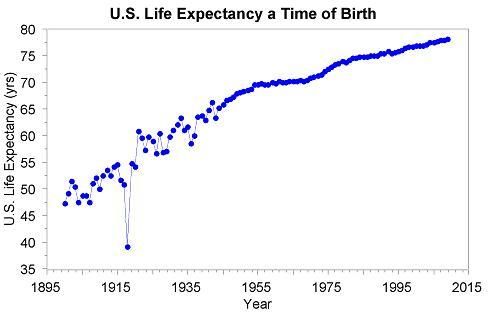

From The Centers for Disease Control, U.S.

This table shows the oft-mentioned shorthand that average life has increased from about 50 years of age to near 80 today. An idea that projects that we are "living longer."

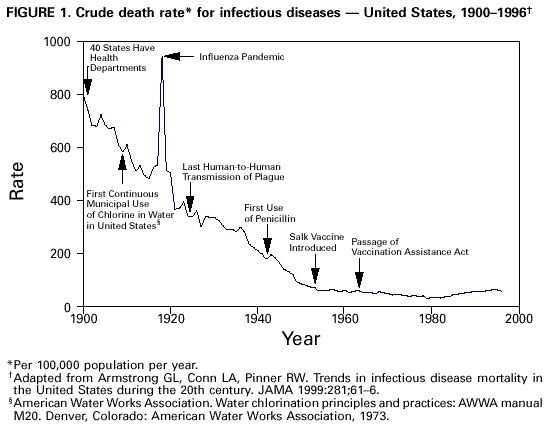

That approximately 30 year improvement in life expectancy is due to increased survival in childhood, mostly increased survival from infectious disease:

Note that the increase in the number of people reaching old

age long precedes almost anything useful that's happened in medical treatment.

Fully 3/4th of the reduced early death occurred before the invention of

penicillin, as well as vaccines for measles, polio, etc..

This improvement in the number of people not dying early actually precedes the 20th century.

In fact, David de la Croiz and Omar Licandro, in 2015,

published a paper titled "The Longevity of Famous People from Hammurabi to

Einstein" which examined a dataset of 300,000 famous people. They showed

that life expectancy (based on what percentage lives to full long life) has

been steadily improving from approximately 1640 onward.

We cannot credit "modern medicine" for our

increased chances for normal life span, or even factors such as sanitation,

food inspection, hand washing and other aspects of hygiene. Improved living has

been going on for centuries. This is important, because some part of us wants

to credit this better chance at full life span to chemotherapy, cardiac bypass,

lipitor and or at least modern screening for disease and early treatment. The data

simply doesn't support this.

So if medicine and modern science are not causing improvements in our odds of living a long life, we have bought into a myth about what science is doing for human health. I believe this myth is what drives the research of the wealthy in California today hoping that they will crack the code of old age within present lifetimes.

May you live as long as Gorgias!

References:

Batrinos, M. The length of life and eugeria in classical

Greece. Hormones 2008, 7(1): 82-83.

De la Croix, D. and Licandro, O. The longevity of famous

people from Hammurabi to Einstein. Journal

of Economic Growth 2015, 20: 263-303.