The

headline almost jumps out at you – “BPA

Substitute Could Cause Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes.” That alarming headline appears in an industry

publication, but the same story was widely reported in

the popular media, which tends to cover science only when they can create scare

stories.

The

article reports the results of a new study

from a group of Chinese researchers on health effects associated with a

substance named fluorene-9-bisphenol (BHPF), which the authors claim is now a

common alternative to bisphenol A (BPA). According to the researchers, and amplified

by the media, BHPF is now used in a wide variety of plastic consumer products

including baby bottles and water bottles that are labelled as BPA-Free.

But

if you see the media articles, you really need to read beyond the scary headlines. What you read may be closer to fake news than

real “news that you can use.” The reason

was touched upon by Popular

Science, which noted that “none of this matters if we’re not coming into contact with BHFP (sic) –

it’s only a potential problem if humans are exposed to it.”

As

it turns out, the evidence that BHPF is used in consumer products is

surprisingly thin. But in spite of the

shortcomings of the research, and the media coverage that lacked much

fact-checking, the theme of the study nevertheless reveals two underlying

truths.

First,

as suggested by the study, replacing BPA may be counter-productive if the replacement

is not well-tested and found to be safe for its use. Second and more importantly, BPA is one of

the best tested substances in commerce. Based

on the extensive scientific data available for BPA, the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) answers the question “Is

BPA safe?” with an unambiguous answer – “Yes.” If we listen to the science, there’s no need

to replace BPA at all, especially with something of uncertain safety.

So,

should you be concerned about BHPF? In a

word, no. You’ll probably never even

come into contact with it.

A

better question is whether you should be worried about products that contain

BPA or are labelled as BPA-Free? The

choice is yours, but keep in mind that BPA is well tested and confirmed to be

safe. The replacements, maybe not so

much.

The Story Behind the Story

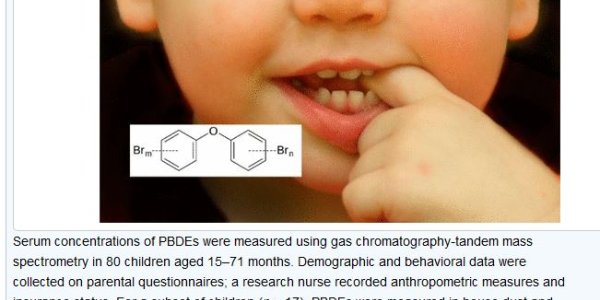

As

a result of recent attention to BPA, many consumer products are now labelled as

BPA-Free, implying they are better or safer than a product made with BPA. Scientifically speaking, that implication

might best be described as a hypothesis that requires scientific data to know

if it is true or not.

The

scientific process is designed to test hypotheses and that’s exactly what many

scientists are now doing with various BPA replacements. New studies are regularly published in the

scientific literature on chemicals that are said to be substitutes for BPA.

The

The

recent study

from these Chinese researchers examined the potential for BHPF to cause

reproductive effects. The substance was

reported to exhibit anti-estrogenic characteristics and the researchers noted

that “[s]erious developmental and reproductive effects of BHPF … were observed

in this study.”

The

results are certainly novel. A search of

PubMed,

which is a comprehensive biomedical literature database, revealed no other

health effect studies on BHPF. And, as

reported by the researchers and the media, the results of this particular study

are also alarming.

But

are the results important for consumers?

As noted by Popular Science, the results only matter if people are

actually exposed to BHPF. If not, the

results are only of academic interest.

Are You Actually Exposed to BHPF?

According

to the researchers, BHPF is used to make a variety of plastics and resins that

are used in a wide range of products. The

San

Francisco Chronicle bluntly stated that the plastics industry

is “manufacturing so-called ‘BPA-free’

water bottles made with an alternative compound called flueorene-9-bisphenol

(BHPF).”

Suspiciously

though, the researcher’s claim of widespread use is not supported by any

reliable references. Of the four

citations provided in the study, none verify any commercial use of BHPF and one

doesn’t even relate to BHPF at all.

The

researchers also report the presence of BHPF in water held in various plastic

water bottles and baby bottles, which may seem to offer proof that BHPF is used

in these common consumer products. But

these results are questionable at best as the actual bottles were never tested

for the presence of BHPF.

The

analytical method for BHPF in water is reported to have an extraordinarily low

limit of detection of 0.1 ng/L (0.1 parts per trillion!), but data to validate

the method are suspiciously sparse.

Making it even more dubious, that limit is 2 to 3 orders of magnitude

lower than the limit of detection for BPA, which has been the subject of well

over a hundred studies by analytical chemists worldwide. Are these researchers really good, just

lucky, or perhaps mistaken about BHPF?

Claims

that BHPF is commonly found in human blood suffer from the same problems with

the analytical method. A more plausible

explanation for the reported findings of BHPF in water and blood was reported

in the Popular Science article: “It’s more likely that the detected

substances were contamination from their lab equipment … or the substances were

misidentified.”

So What Can We Learn From the Study?

The

claims that BHPF is in widespread use and that people are commonly exposed to

BHPF are simply not credible. In spite

of the alarming headlines about serious health effects from BHPF, there is no

sound, scientific basis for alarm.

Nevertheless,

the new study can be instructive.

Although BHPF is not a concern, the researchers, as highlighted in Popular

Science, have identified an important underlying issue:

“We think,” wrote Hu to PopSci, “that toxicity of substitutes should be

assessed comprehensively, and regulations for substitution of chemicals should

be developed in the future.”

More

eloquently, Professor Richard Sharpe, Group Leader of the Male Reproductive

Health Research Team at the University of Edinburgh highlighted

the two underlying truths behind this new study:

“As far as regulatory bodies such as EFSA and

FDA are concerned there is no convincing evidence for replacing use of

bisphenol A by substitute chemicals, though environmental pressure groups

continue to press for a ban on use of bisphenol A and its replacement. This study highlights that such replacement

may be jumping ‘out of the frying pan and into the fire’, by showing that one

of the suggested replacement chemicals may itself have potential to cause

adverse endocrine effects, although it is unclear from the studies if humans

would be exposed sufficiently for this to cause harm.

“A huge amount is known about bisphenol A in

terms of its activity, human exposure, metabolism etc, and it is this level of

understanding that has enabled regulatory bodies to determine the risks that

our exposure poses to our health. In

contrast, we have very little understanding about the suggested replacement

chemicals. Therefore this study, which

appears generally well-designed and executed, reminds us that replacing use of

one chemical by another needs to be an evidence-led process, otherwise we may

do more harm than good.”

Perhaps

the most important lesson to learn from this recent study and the alarming

media coverage that ensued is to not take scary headlines at face value. The story behind the story may be far more

important than the story itself.