A

recent

analysis of published data on human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) revealed more

than 140 studies with over 85,000 data points from 30 countries. Taken together the data show that exposure to

BPA around the world is hundreds to thousands of times below the

science-based safe intake limits set by government bodies.

That’s

already far more data than is available for most chemicals, but the data just

keeps on coming. Health

Canada recently released an important new report with data

on exposure of Canadians to a variety of chemicals. Along with BPA, the Fourth

Report on Human Biomonitoring of Environmental Chemicals in Canada

provides exposure data on 53 other environmental chemicals for more than 2,500

participants throughout Canada.

It’s

important because without knowing how much of which chemicals we’re exposed to,

it’s difficult to know whether those chemical exposures are safe or not. After all, dose does matter. If you’re not sure about that, imagine taking

a bottle of aspirin next time you have a headache. You might get rid of your headache, and a lot

more. In particular you might get rid of

your life since two aspirin are safe and effective for the headache but a whole

bottle of aspirin could kill you.

The

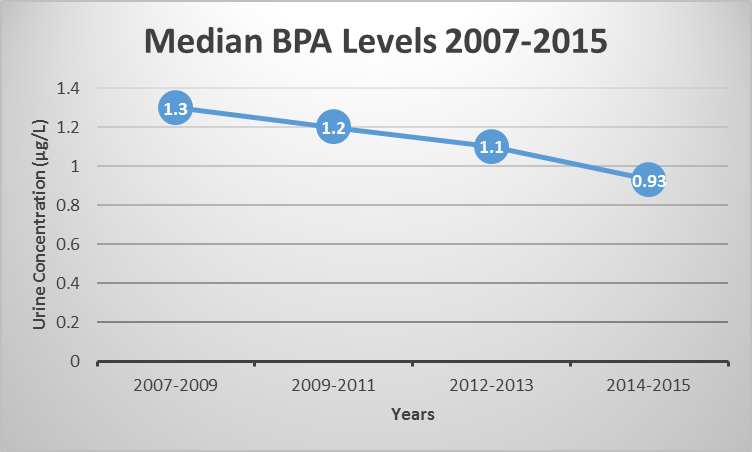

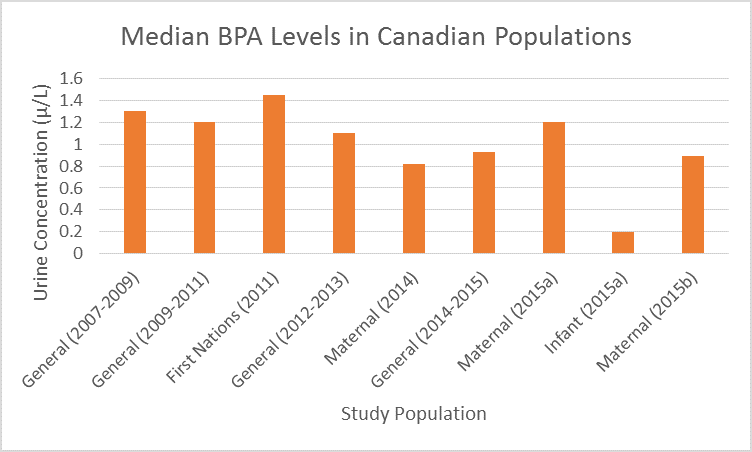

new report is the fourth in a series that together provide data on BPA exposure

to the general Canadian population (ages 3-79 years) over 8 years

(2007-2015). The new data confirms that

exposure of Canadians to BPA continues to be very low. Similar to what has been reported in other

countries, typical exposure to BPA in Canada is more than 1,000 times below the

safe intake limit set by Health Canada.

In

addition, the new data adds to what is probably the most comprehensive database

on exposure to BPA for any country.

Canadian researchers have also published results from four large-scale

exposure studies on potentially sensitive subpopulations (pregnant women and infants)

and the First Nations people.

The

data from all reports consistently show that exposure of Canadians to BPA is

far below Health Canada’s safe intake limit for all of the populations

studied. Importantly, the temporal data

indicates that exposure to the general Canadian population is decreasing with

time, moving in the direction of a higher margin of safety.

What Did Health Canada Do?

Since

2007, the Canadian government has conducted the Canadian Health Measures Survey

(CHMS) to collect information on the general health of Canadians. The survey collects baseline data and risk

factor information relevant to general health, chronic and infectious diseases,

fitness and nutritional status.

The

survey also collects blood and urine samples in its biomonitoring component for

analysis of various environmental chemicals, which is where BPA enters the

picture. It’s primarily used to make

polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resins and those materials are widely

used

in products that make our lives better and safer every day. Our use of those products raises the

potential for exposure to trace levels of BPA.

Along with benchmarking chemical exposures, the biomonitoring data can

be used to assess the need for policies to protect the health of Canadians from

exposure to chemicals.

What Did The Media (Mis)Report?

Most

likely you didn’t see any of the limited media coverage on the report, but you

didn’t miss much since it appears the media didn’t actually read the

report. The headlines proclaimed that

Health Canada found BPA in the blood of more than 90% of Canadians. That may be an eye-catching headline, but

Health Canada didn’t actually look for BPA in blood, and for good reason. Had they done so, they almost certainly would

not have found any.

It’s

well

known that our bodies efficiently convert BPA to a

biologically inactive metabolite after exposure. Because what goes in (exposure) is quickly

eliminated in urine where it’s easy to measure, experts from around the world

agree that “urine

is the best matrix for epidemiological assessment of exposure to BPA.”

And that’s exactly what Health Canada

did.

What Does The Data Mean (And Not

Mean)?

Perhaps

the most glaring omission from the media stories is a point so important that

Health Canada included it in its short “Backgrounder”

on the report.

“It

is important to note that the presence of a chemical in a person’s body does

not necessarily mean that it will affect their health.”

The

report documents that BPA, in the form of its metabolite, is present in urine, which

means exposure did occur. But what does

that data mean for our health?

Fortunately

for BPA, it’s relatively easy to interpret the data with respect to

health. Along with other government

bodies, Health Canada has already determined a safe

intake level for BPA.

In a previous study, Health Canada researchers further determined the

amount of BPA that would be measured in urine if exposure occurred at the safe

intake level. That value is known as the

Biomonitoring

Equivalent (BE) for BPA.

Comparison

of the new data with the BE reveals that typical exposure to BPA in Canada is

fully 1,000 times below the safe intake level set by Health Canada. The data strongly supports Health Canada’s earlier

conclusion that “Bisphenol

A does not pose a risk to the general population, including adults, teenagers

and children.” But you wouldn’t have found that in the media

coverage either.

How Does The Data Compare With

Previous Studies?

With

the data provided in this new

report, Health Canada now has data on exposure of the

general population of Canadians to BPA over an 8-year period from

2007-2015. Although Health Canada has

previously concluded that BPA does not pose a risk to the general population,

exposure data over extended periods of time is important to know whether there

are any significant changes in exposure.

Changes are not necessarily good or bad, but might be signals that

further evaluation is needed.

A

trend towards higher exposure might suggest the need to reevaluate Health

Canada’s conclusion, or to consider whether any policies should be implemented

or revised to limit exposure. In

contrast, a trend towards lower exposure strengthens the conclusion by

increasing the margin of safety and indicates that existing policies are

adequate to control exposure.

The

data on BPA exposure from the four reports shows a clear trend towards lower

exposure over time. Although the data

cannot inform on the specific source of exposure or why exposure is decreasing,

the data does indicate that current use patterns for BPA and policies to

control exposure are adequate to ensure a wide margin of safety.

In addition to the series of reports on the general

population of Canadians, other Canadian government researchers have published

four other studies that provide BPA exposure data on potentially sensitive

subpopulations. These include three

studies on pregnant women (1, 2, 3), one of which

included data on infants,

and a study on the First Nations people. Perhaps not

surprisingly, exposures are similar for all populations examined with the

notable exception of infants.

It is generally believed that most exposure to BPA is

through the diet. Since infant diets are

generally different from adult diets and more limited, infant exposure to BPA

will not necessarily be the same as adult exposure. Although data is limited to one study, infant

exposure is significantly lower, which suggests that existing policies to

control exposure are adequate for infants as well as adults. The data also indicates that Health Canada’s

conclusion that BPA does not pose a risk to Canadians is applicable to infants.

How

Does The New Data Compare With The Rest Of The World?

It’s

not just Canadians who need not be concerned about BPA. A recent

analysis from a group of researchers in China revealed that

exposure to BPA is very low in every one of the 30 countries where it’s been

measured.

That

analysis included data from studies on exposure to BPA that have been published

in the peer-reviewed scientific literature.

All told, the researchers found more than 140 studies with data on over

85,000 participants in 30 countries. The

results from the new Health Canada study reaffirm that exposure of Canadians to

BPA is similar to the exposure levels measured in the rest of the world.

The

extensive data on exposure to BPA from all of these studies leaves little doubt

that human exposure to BPA is extremely low and far below science-based safe

intake limits. Perhaps the US Food and

Drug Administration says it best in a Q&A on its website: Is

BPA safe? Yes.