As Carl Sagan once said, “extraordinary claims require

extraordinary evidence.”

You may have recently read some extraordinary claims that

total sperm count has dramatically declined among “Western” men and that

endocrine disrupters - but only the synthetic kind, not natural ones - are the

reason. The extraordinary evidence is lacking.

Scientists

from the Harvard GenderSci Lab are putting the brakes on the

alleged “apocalyptic” trends in male reproduction.

The peer-reviewed

Harvard paper, by Marion Boulicault, Sarah Richardson, and colleagues,

re-evaluated the meta-analysis by authors Levine et al. in 2017 and found

significant inconsistencies and biases in the methods and assumptions used by Dr.

Shanna Swan and colleagues to make their finding.

Boulicault and

colleagues also propose a more plausible framework for interpreting population

trends in human sperm counts that they believe offers “a more analytically

rigorous, empirically driven” framework for interpreting population-level

trends in human sperm counts than that posed by Levine and colleagues.

Importantly, the new examination

of the same data and background literature as used in the 2017 meta-analysis casts

doubt on the conclusions reached by its authors.

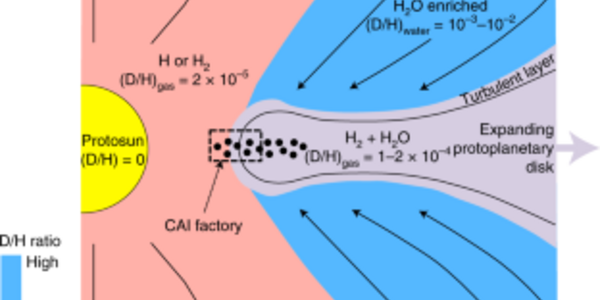

The number of sperm samples per country over the period 1973–2011 included in the 2017 meta-analysis. The global coverage is mottled and asymmetric and Levine et al. concede that sperm count in ‘Other’ countries is sparser than ‘Western’ countries but don't acknowledge inconsistent data in Western countries. Instead of applying to all men it can really only describe general population trends in sperm count within Denmark.

The new paper points to

a number of things to consider before conclusions on decreases in sperm count

or male fertility can be drawn.

- Current Western average sperm counts are well within

the normal range defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (15 to 259

million per ml). - Linking male infertility to sperm count is too

simplistic. Men with low sperm counts can conceive, while others with higher

counts cannot. - If there was an increase in male infertility, it would

show up in the fertility data. Yet, there is no proportional increase in

infertile men that would be expected if the decline in sperm count claimed by Levine

and colleagues was really occurring. - The use of arbitrary categories like “Western”

(predominantly white) and “Other” obscures key underlying data. For example, if

the data is evaluated by specific geographic region, there was no sperm count

decline for fertile North American men. Yet, there would have to be if

endocrine disruption was happening. - There appears to be no causal relationship between “endocrine

disruptors” —

exogenous chemicals that have been studied for their potential to mimic

endogenous hormones and bind to protein receptors — and any barometer of sperm health, including sperm

count, sperm motility, and fertility. - Levine and colleagues had no data to support the claim

that ‘”Western” men face increased exposure to environmental pollutants

compared to men in “Other” nations, as explanation of the differences between

sperm counts. Instead, since 1973, exposures to environmental pollutants have

plummeted. Data on exposure would be required to support a claim that exposure

is connected to any sperm count decline.

As the Harvard authors

conclude, “researchers must take care to weigh hypotheses against alternatives

and consider the language and narrative frames in which they present their work.”

Objective, sound science

should drive decision-making and public discourse. Presentation and

interpretation of scientific studies must be done carefully to avoid making provocative

yet unfounded public claims, especially when a study has not established sufficient

causal links to human health effects.

To do otherwise is both concerning and a

disservice to the public.