Ecology & Zoology

"Male of Dosidicus are gentlesquid."

That was today's last hypothesis. In fact, it was the very last sentence of the last slide of the last talk of the first

day of the 5th International Symposium on Pacific Squid. It was

announced by the venerable Dr. Chingis Nigmatullin, as an explanation

for the fact that 90% of all jigged Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas) are females.

Nigmatullin suggested that male Humboldt squid are such caballeros

that they always allow the females first bite when food appears. In the

case of fishing lures, this leads to the unfortunate and

disproportionate demise…

Well! The last day of the squid fertilization workshop was just as exciting, in its own way, as Sunday's fishing excusion. The workshop's dozen participants hail from Mexico, Peru, Brazil, USA, Germany, Russia, and Spain. But our passion for cephalopod reproduction is as pure as our backgrounds are diverse. That's right, we are all obsessed with squid sex. So obsessed that we will make ourselves late for lunch with concerns about the chemistry of egg masses, and debate ommastrephid paralarval nutrition well into the night. Yesterday morning we showed each other videos of egg…

Today is the last of the International Cephalopod Awareness Days: Squid Day! Naturally Squid-A-Day is feeling very festive. Sorry I missed Day Two--yesterday was the first day of the squid workshop and I was exceedingly occupied.

Fittingly enough, today was the workshop's pratical day--the plan was to go out fishing, catch a mature female Humboldt squid, and perform in vitro fertilization with all the brightest stars in the field.

Well, everything went perfectly, except three hours of fishing yielded not a single squid.

In all other regards, it was a lovely day out on the water of the open…

Octopus Day 2010 finds me in La Paz, Mexico, eating a homemade corn tortilla with Oaxacan cheese. It is extremely delicious. After the trip to Madagascar, where I found that dairy is just not part of the culture, it pleases my lactophilic sensibilities to be in the land of queso and paletas.

But that's just a fringe benefit. I'm here for the cephalopods, of course. Although today was a travel day, and the squid workshop doesn't start until tomorrow, I did wear my Sir Octopus shirt with pride.

"Anti-science" or "cautious" ... how you regard skeptics of positions that are ethically or scientifically subjective is often a matter of how you already believe. If you are a Republican concerned about the ethical implications of human embryonic stem cell research, whole books can be written on how Republicans hate science. But if you are in astronomy and have watched every program started during the Bush years get gutted since Democrats took control of Congress, you might think Democrats hate Congress(1) more. In reality there are legitimate issues involved and it is up…

Humboldt squid: news when you see 'em, news when you don't.

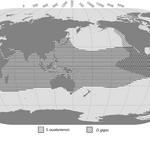

Now, the mystery deepens: It seems the Humboldt squid, the locusts of the ocean, have vanished from the Pacific north of California this year.

Nice epithet. Just one correction: the article refers to Humboldt squid as "tropical cephalopods." Cephalopods yes, tropical no. It's true they are found in the tropical Pacific--I've caught them there myself--but they become larger and more abundant as you move away from the tropics to the north and south. They are actually a subtropical/temperate species. Another related species,…

Evolutionary detectives have used century-old bits of DNA from museum specimens to find a place for the extinct passenger pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius, in the family tree of pigeons and doves, identifying for the first time this unique bird's closest living avian relatives. The new analysis reveals that the passenger pigeon was most closely related to other North and South American pigeons, and not to the mourning dove, as was once believed. To find the passenger pigeon's place in the evolutionary history of pigeons and doves, the researchers compared sequences from two of…

US News&World Report has a nifty writeup from the NSF about research on Humboldt squid, featuring my PhD advisor and various collaborators. Both the title and the subtitle make me laugh:

Exploring How Jumbo Squid Use Oxygen to SurviveResearch could explain how ocean ecosystems work

The title just sounds boring, because, c'mon, don't we all use oxygen to survive? (Except obligate anaerobes.) And the subtitle is just meaninglessly all-encompassing. Research could explain how thingwork? Really?

But I feel for the editors, trying to come up with headlines, because the…

If you're a squid, that is.

Apparently squids of the species Martialia hyadesi like to eat oily fish. They're messy, so they leave oil in the water, which floats to the surface. Grey-headed albatrosses, meanwhile, like to eat squid. They cue in to these oil slicks and dive to catch the squid, which are probably still in a food coma after that nice big fatty meal.

I made up the bit about a food coma. But everything else is in this paper:

The characteristics of the squid and their proximity to the surface suggest that the birds locate squid concentrations by olfaction and catch them by…

Humboldt squid have gotten so much press off the west coast of the Americas that pretty much any big squid found in these waters is immediately labeled a Humboldt. For example, a Mr. Anderson and his dog Chance recently found a Big Squid Strayed Too Far North on an Alaskan beach:

Sherry Tamone, a professor of marine biology at the University of Alaska

Southeast, looked at Anderson's pictures and guessed the creature was

likely a very large humboldt squid that had accidentally hitched a ride

on a dead-end warm current headed north.

Although Humboldts have certainly made their way into Canada…