Drosophila flies lose long-term memory of a traumatic event when kept in the dark, and the authors of a new study link that to a specific molecular mechanism responsible.

Memories are difficult to erase but breakthroughs could be important for sufferers of trauma, because while most normal events won't be recalled even the same day, a particularly shocking event may be consolidated into our long-term memory, whereby new proteins are synthesized and the neuronal circuits in our brain are modified.

Such memories may be devastating to a victim, potentially triggering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Yet physiologically speaking, keeping a memory is far from a trivial process; active maintenance is required to keep the changes, protecting against the constant cellular rearrangement and renewal of a living organism. Despite the importance of understanding how memory works in the brain, the mechanism by which this occurs in humans is not yet understood.

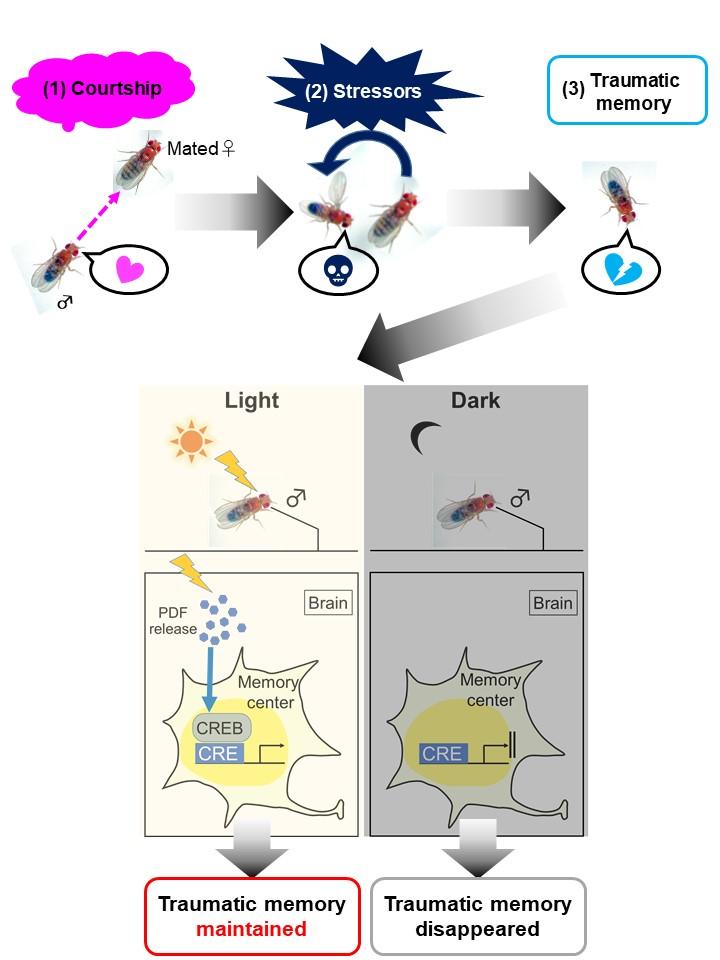

Pigment-dispersing factor regulated the transcription of a protein called the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB). Image: Tokyo Metropolitan University

Studies on flies are common, though, and it is known that light, particularly the cycle of night and day, plays an important role in regulating animal physiology. Examples include circadian rhythm, mood and cognition. A team led by Prof. Takaomi Sakai from Tokyo Metropolitan University set out to study how light exposure affects the memory of diurnal Drosophila fruit flies. As an instance of long-term memory or trauma, they used the courtship conditioning paradigm, where male flies are exposed to female flies which have already mated. Mated females are known to be unreceptive and exert a stress on male flies which fail to mate. Once the experience is committed to long-term memory, they no longer attempt to court female flies, even when the females around them are unmated.

The team found that conditioned male flies kept in the dark for 2 days or more no longer showed any reluctance to mate, while those on a normal day-night cycle did. This clearly shows that environmental light somehow modified the retention of LTM. This was not due to lack of sleep; flies on a diurnal cycle were slightly sleep deprived to match with flies in the dark, with no effect on the results. They focused on a protein in the brain called the Pigment-dispersing factor (Pdf), known to be expressed in response to light.

For the first time, they found that Pdf regulated the transcription of a protein called the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in the mushroom bodies, a part of the brain of insects known to be implicated in memory and learning. Thus, they identified the specific molecular mechanism by which light affects the retention of long-term memory.