The National Grid Service in the UK and the TeraGrid in the U.S. have joined forces to help University College London (UCL) scientists shed light on how life on Earth may have originated.

Deep ocean hydrothermal vents have long been suggested as possible sources of biological molecules, such as RNA and DNA, but it was unclear how they could survive the high temperatures and pressures that occur round these vents.

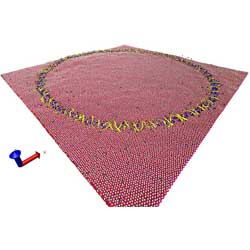

Peter Coveney and colleagues at the UCL Centre for Computational Science have used computer simulation to provide insight into the structure and stability of DNA while inserted into layered minerals.

“Computational grids are only now being made easy to use for scientists, enabling simulations of sufficient size to model these large biomolecule and mineral systems,” Coveney explains.

Previous experimental studies have shown that molecules such as DNA can be inserted into minerals called layered double hydroxides, but no one has thus far been able to show at the level of atoms and molecules how the DNA interacts with the mineral, or how the DNA might look inside the mineral layers. These minerals would have been common in the earliest age of Earth, around 2500 million years ago.

Coveney’s simulations reproduced the high temperatures and pressures that occur around hydrothermal vents, showing that the structure of DNA inserted into layered minerals becomes stabilized at these conditions and therefore protected from catalytic and thermal degradation.

“Grids of supercomputers are essential for this kind of study”, says Coveney. “The time taken to run these simulations is reduced from the years that a desktop computer would take, to hours by using the many thousands of processors made available across continents.”

Working together with colleagues at Nottingham and Durham Universities, Coveney’s group has been researching routes to the origin of life for many years, studying the way that genetic information may have arisen and been replicated, as well as how small molecules may have formed.

– Gillian Sinclair, National Grid Service, 'International Science Grid This Week'