Gary Larson tapped into the universal absurd.

Charles Schulz helped us identify with the underdog in us all. And Bill

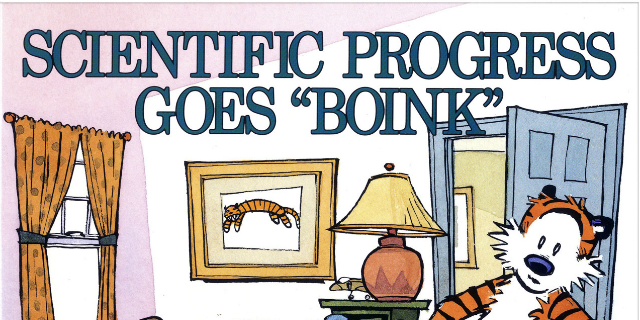

Watterson accurately represented a father’s profound and boundless knowledge of

the universe, as in Calvin’s dad’s explanation that ice floats because, “It’s

cold. Ice wants to get warm, so it goes to the top of liquids in order to be

nearer the sun.” Or his explanation of relativity: “It’s because you keep

changing time zones. See, if you fly to California you gain three hours on a

five-hour flight, right?”

Again, and in the words of another cartoon sage,

“It’s funny because it’s true.” How true? Well, THIS

shows that preschool-aged children blindly accept adults’ explanations of

things without considering how the claims match real-world evidence. So

Calvin’s dad is scientifically copacetic: as we see in the comic, six-year-old Calvin

is just starting to tentatively doubt his dad’s explanations that, for example,

a bridge’s weight limit is determined by, “Driving bigger and bigger trucks

over the bridge until it breaks. Then they weigh the last truck and rebuild the

bridge.”

So will kids younger than Calvins believe

anything we tell them? When we wag our parental mouthparts in a preschooler’s

general direction, does the content matter? A study on

early view at the journal Child

Development says yes, and the implications for how kids use parents as

guides through the purgatory of questionable information goes far beyond

cartoons.

Compare the following answers to the question

“why does it rain?” used in the study:

1. Sometimes

it rains because it is wet and cloudy outside, and water falls from the sky.

When water falls from the sky it is called rain and rain gets us all wet.

2. Sometimes

it rains because there are clouds in the sky that are filled with water. When

there is too much water in the clouds, it falls to the ground and gets us all

wet.

The first is “circular” – notice that it

doesn’t really answer the question. In the experiment, the first answer was

attributed to a picture of a fictional female “explainer” in a black shirt and

the second answer was attributed to a female explainer in a green shirt. Then

the kids were given a picture of some new, ambiguous object. The experimenter

pointed out something about the object, for example saying, “I wonder why it

has a round thing there?”

The black-shirt and green-shirt explainers

gave their opinions about the object’s “round thing” and in this case both

explanations were equally valid: “It has a round thing so it can spin on the

table” or “it has a round thing so it can roll on the table.”

Which explainer did kids believe? You’re

probably ahead of the punch line: both 3yo and 5yo kids preferred the “round

thing” explanation delivered by the explainer who had come correct with a

linear explanation for the “why does it rain” question. They went back to the

person who they knew delivered the best information.

Here’s an interesting part: 5yos knew in their conscious minds which

explainer was better – when asked which was best, they pointed at the

non-circular explainer; 3yos couldn’t point at the better explainer, but their

unconscious preference for the better explainer showed that something

functioning below the surface of their developing, Dora-obsessed minds knew the

difference.

The authors from Boston University write, “Taken

together, preschoolers are surprisingly selective, not only in using single

words but also in using entire utterances to judge an informant’s credibility.”

Read that again: the quality of the

explanations you offer to your children will influence their perception of your

credibility. Not only that, but your explanations will influence how likely

your kids are to ask you for explanations in the future.

Here’s the funny thing: according to

this study, Calvin’s dad was spot on. Though his explanations may have slightly

stretched what we adults narrowly think of as scientific credibility, they are

linear, logical and – at least to the brain

of a young child who hasn’t yet pruned branches from the tree of possibilities

– perfectly plausible. That’s why Calvin goes back for more: the quality (if

not content) of his dad’s explanations allow dad to continue as Calvin’s oracle

of information.

Make sure your explanations answer the

question instead of parading around the topic and you can do the same.