Yours truly has been watching telly again! (I hope no-one will get the idea that the couch potato might be a significant source of starch.)

This time, on our local BBC news service, we hear how researchers at the University of Portsmouth Institute of Biomedical and Biomolecular Science are cooperating with their Institute of Marine Sciences to harness the Gribble.

And what can a Gribble do? As Max Bygraves sang:

Gilly Oh golly, oh I love my lolly,

Come winter and summer and spring.

But when you are done it’s about as much fun,

As a yo-yo without any string.

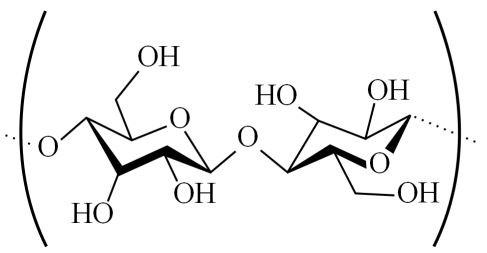

Now cellulose, like starch, is a polymer of glucose, but while in starch the glucose units are tagged together in an up-up-up configuration, in cellulose they alternate in an up-down-up-down manner. This latter configuration not only forms much more stable crystallites, but requires greater enzymatic sophistication to digest, and the gribble Limnoria is one of the very few animals that produces its own cellulase.

The team at Portsmouth have isolated from the gribble DNA which encodes for the enzyme b-1,4-endoglucanase (to give it its proper name). The aim is to recycle low quality wood into fuel within 10 years.

Previously, gribbles were studied at Portsmouth with the aim of preventing their habit of destroying marine wooden structures, and the BBC showed us the devastation they caused to piers at seaside resorts such as Yarmouth. These little crustaceans are isopods, which means that they are related to the land-dwelling sowbugs and pillbugs, as they are known across the pond.

Here in Reading the land version are called by the peculiar local name cheeselogs, but the general name for them in England is woodlice. But from their habits, it seems that wood lice would be a better term for their marine relatives.