Exposure to media that promotes

conspiracy theories may increase belief in them, but exposure to

debunking information can decrease that belief, a

new study has found.

The report, published in the

January-March edition of the journal Communication Quarterly

and conducted by researchers at the University of Missouri and

Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus, suggests that messages

can influence peoples' beliefs, even in a fragmented media world.

Researchers conducted two experiments.

In the first, subjects learned about the “Birther” conspiracy

suggesting that president Barack Obama is not a legitimate U.S.

citizen and therefore does not qualify for the presidency.

In the second, subjects were exposed to

the “Truther” conspiracy, which alleges that the administration

of former president George W. Bush was involved in producing or

abetting the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Why use these two conspiracies? Because

of their political implications. People tend to adopt conspiracy

theories because

they feel marginalized by the existing political order. Though

the spread of conspiracies does not always fall along partisan lines,

the Birther movement has mostly been taken up by the political right,

while the Truther movement emerged originally from the left.

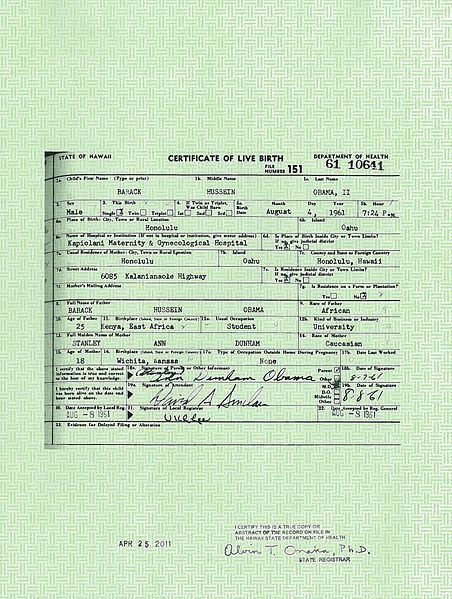

Barack Obama's long-form birth certificate. Courtesy of whitehouse.gov.

Participants in both experiments were

divided into three subgroups: one that was exposed only to messages

that confirmed the conspiracy theory, one that was exposed to both

confirming and debunking messages, and a control group that was given

totally unrelated material to watch or read. All of the groups were

asked about their level of belief in various aspects of the

conspiracy theories beforehand and afterward.

The results were a bit of a mixed bag.

As expected, belief in the Birther conspiracy rose among those

exposed only to confirming information, while it fell significantly

for everyone else.

But things were a bit different with

the Truther conspiracy. In that experiment, all three groups showed a

marked increase in belief; even the control group experienced

a slight uptick.

Perhaps even more interesting was that

the changes in peoples' opinions weren't affected by party

affiliation, as one might presume from the nature of the

conspiracies. Republicans and Democrats were both as likely to

believe (or disbelieve) a given conspiracy theory based solely on

which experimental condition they happened to be placed into.

Minimal Media Effects?

Since the early 1900's, communication

scholars have proposed a slew of hypothesis to explain how mass media

influence populations. One of the earlier models is known as the

“minimal-effects” model. It is basically what it sounds like:

people make their own decisions about what to believe, and mass media

have little influence over those decisions.

The minimal-effects model was largely

abandoned as more nuanced explanations came along. Over the last few

years, though, it

has seen a resurgence because of the changing media landscape

brought on largely by the Internet.

In today's environment, the argument

goes, people can choose to watch, read and listen to messages

tailored to their interests and values. There is so much selection,

in fact, that a person can wrap herself in a cocoon of media that

rarely challenges her beliefs. You may have heard this described as

the “echo chamber,” a room in which the only thing you can hear

is your own voice bouncing back at you.

To be sure, the minimal-effects model

doesn't posit that a person will never encounter any dissenting

messages. Rather, it proposes that she will be “more attuned to

resisting any messages that prove discrepant.”

The Communication Quarterly

study, however, adds to the challenges for modern minimal-effects

proponents. After all, if peoples' preexisting positions led them to

resist media messages, then there should have been major differences

in how Republicans and Democrats reacted to the Birther and Truther

conspiracy theories and the debunking evidence. Yet both parties were

equally influenced by the messages.

The authors do note one particular

weakness to their experiment: the participants were a median age of

about 21 years old in the Birther group, and about 19 years old in

the Truther group. Since young people tend not to be as strongly tied

to political affiliations or ideas as older people are, it's

difficult to extrapolate the strong influences seen here to all of

society. The authors admit that “the finding that prior political

affiliation does not moderate the media effect may be a product of a

sample with attitudes that are more malleable than the general

public.”

More confusing still may be what this

study means for science communicators and others seeking to debunk

false or misleading claims with evidence. Although the subjects

exposed to evidence against the Truther conspiracy were less liable

to be convinced by the theory than those who only received

pro-Truther messages, the fact remains that both groups increased in

their buy-in of the conspiracy overall.

The researchers write that this could

have had something to do with the specific presentation of the

counterarguments, which were given in the form of a Popular Mechanics

article. “Perhaps a more sophisticated audience taking more time to

carefully consider the evidence would have found the debunking

evidence more persuasive,” they write.

Perhaps. Even so, is it likely that

media consumers are on the whole “more sophisticated,” or that

they would take the necessary time and care? On the other hand, could

the fact that counterarguments to conspiracies did have an effect in

both experiments mean that debunking efforts, even if not perfectly

effectual, are nevertheless a worthwhile cause?

The answers to these and other

questions may have profound implications for the effectiveness of

science communicators as they craft messages for both public

officials and general audiences.