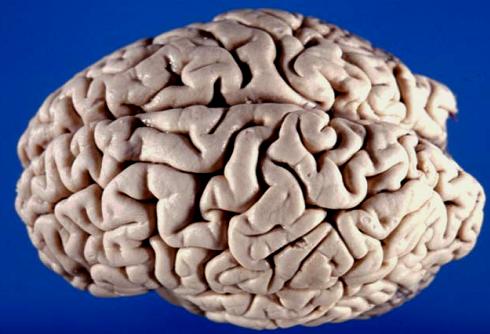

Brain

training has come into the spotlight with Tuesday’s announcement

by the Federal Trade Commission that the popular website Lumosity will be

forced to pay a $2 million settlement for making false advertising claims.

Lumos

Labs, Inc., which does business as Lumosity, was ordered to pay the money by

the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California to settle an

FTC complaint that the company claimed its games could improve everyday

tasks, delay age-related cognitive declines, and improve a variety of other

mental impairments. The FTC also charged the company with failing to disclose

that it had solicited testimonials through contests that awarded major prizes.

Lumosity

sells games to customers that are ostensibly designed to target particular

cognitive skills. The user takes a test to get “baseline” scores on these skills,

and then begins playing. The games get more difficult as the user plays them,

and as a result the scores (should) improve.

The

company has long used scientific terms in a dubious manner to increase its cred

among potential customers.

One

of its go-to words has been “neuroplasticity” - a fancy way of saying that the

structure of your brain changes with your experiences.

It’s

true that the connections in your brain change when you learn a new language,

when you witness a traumatic event…and when you play computer games.

It’s

also true that some skills are broadly applicable. Many are things we spend

years in school to perfect: reading, writing, arithmetic, teamwork, following

directions, critical thinking.

These

are all forms of “brain training” that take advantage of “neuroplasticity.” But

we generally don’t gussy them up in scientific jargon. We call them “learning.”

Part

of Lumosity’s charm, though, is the plausibility of its claims. Some seem

commonsensical. Everyone knows that practicing a skill will improve it. It’s

also generally accepted that challenging one’s mind and keeping active can

stave off (or at least slow) some kinds of cognitive declines.

But

Lumosity’s pitch goes beyond this. Its central argument is that its regimen of

simple games is broadly transferable to other skills, and that those games are

better than other forms of activity.

Seen

in this light, the company has a tougher row to hoe. In real life, we don’t

suggest that learning to ride a bike will make you better at driving a car.

If

you want to learn to drive a car, you drive a car.

Lumosity

has gone to great lengths to bolster its claims of validity, conducting and

pointing to numerous examples of peer-reviewed research.

As

it turns out, there is a wealth of research on the subject of cognitive

training. The problem is that most of it remains mixed and

correlative. On the specific question of generalizability – the

transference, say, of working

memory skills to intelligence – the data so far are mostly negative.

That’s

bad news for Lumosity, because its model relies on the assumption that skill in

its games is generalizable to other areas of players’ lives.

And,

of course, all those negative studies (here’s another) don’t

make the cut on Lumosity’s

reference list.

Even

after its regulatory slap-down, the company’s home page continues to tout its

scientific bona fides.

As

of Saturday, the website displayed a

reference to an in-house study it conducted comparing users who played Lumosity’s

games against a control group that was given crossword puzzles.

The

study, published in September in the

journal PLOS ONE, found

that Lumosity players did better on an assessment given after ten weeks of

playing. It also showed an increase in the post-test assessment of crossword,

but with an edge in most areas for the Lumosity group.

Though

this study is internally consistent, it is not (as so many of Lumosity’s ads

would have you believe) neuroscience. Nor are most of the studies published by

Lumos Labs. The bulk of them more accurately fall under the social sciences and suffer many of

the traditional limitations of such research.

For

instance, the participants in this study were chosen randomly, but they were

drawn from a pool of people who had already signed up to Lumosity. Since it

wouldn’t be possible to blind the participants (that is, they would know which

group they were in by virtue of the games they were allowed to play), it’s not

much of a leap to presume that the crossword group might have started with

lower expectations for the group they found themselves in, while the reverse

would be true of the group allowed to play Lumosity games.

Then

there’s the problem of inherent researcher bias. Industry-funded research is

notorious for this, and begs to be replicated by an independent lab.

And,

as usual, this study is only correlative. That key element of causation remains

lacking.

Though

Lumosity’s devotion to science remains merely self-aggrandizing, it is playing

by the rules. The now-mandatory caveat emptor language is included on its home

page:

“These

results are promising, but we need to do more research to determine the

connection between improved assessment scores and everyday tasks in

participants’ lives.”

More

research is needed indeed. Whether any aspect of the brain training fad pans

out scientifically remains to be seen.

Until

then, the only thing Lumosity customers are definitely getting is the privilege

of paying to flip tiles.